A walk from Waterloo to the University of Waterloo

Waterloo is a small city that has owed much to the rise of the University of Waterloo over the last half century. Uptown Waterloo is the thriving, if small, downtown area. Waterloo has 100,000 residents and the University of Waterloo has 30,000 people. It’s less than 2 km between Uptown and the main UW campus. Let’s take a walk from one to the other.

Transit infrastructure, not just transit

The streetcars that crisscrossed North American cities and towns in the late 19th and early 20th centuries were generally built and run by private companies, and operated at a profit. With the rise of the private automobile and due to other factors, they were no longer able to turn a profit, even in the cities in which streetcars were not deliberately run into the ground. I don’t think cities realized at that time that the infrastructure of the streetcar lines may have actually been worth paying for — and not just something to be allowed if paid the usage fees by streetcar companies. And so the infrastructure was swept away with the streetcars, which paved the way (no pun intended) for the downturn of urban areas and boosted suburb development.

Fast forward to now. Many people still participate in discussion of, and decisions about transit in North America without understanding that transit is not just about moving people effectively. From such a point of view, it can make sense to advocate for high-frequency buses and not much else in many cases. (Of course, there are also factors such as comfort and simplicity to consider.)

The other side of transit is infrastructure. Transit infrastructure, generally rail-based, changes the fabric of its surroundings. It transforms the geography, and attracts disproportionate development to its stations or corridors. Once built, it is taken as a permanent and reliable connection and short-cut between disparate places. It is visibly in place, a financial and social investment that is both useful and that cannot be easily picked up and moved. In other words, it is infrastructure. And such infrastructure is central to reclaiming an urban landscape.

We should stop talking about just transit, and start talking about transit infrastructure. The way discussions are framed makes a difference, and currently discussion about transit allows the ignorance of all the implications of transit beyond the movement of people. The only way to build liveable cities in North America that are not car-dependent is by building strong transit infrastructure. Transit can only follow, while transit infrastructure leads.

Quantifying the bus experience

Yesterday I took the iXpress bus from Uptown Waterloo to Conestoga Mall (with only four stops in between). In those 20 minutes I counted around 130 minor rattles of the bus, and 80 major rattles. So on average, that’s around a rattle every 6 seconds, with a major one every 15 seconds. It’s not surprising why it’s difficult to read on a bus, and why headaches are a frequent result of the ride.

Waterloo Region LRT as a tipping point for transit

On June 24, Waterloo Regional Council nearly unanimously endorsed the plan for light rail between Waterloo, Kitchener, and Cambridge. Pending firm commitments from provincial and federal governments, the first stage will consist of light rail between Waterloo and Kitchener and temporary adapted bus rapid transit between Kitchener and Cambridge.

The case for LRT in the region is solid, but it is of course unusual for North America to date in how proactive it is. the transport politic wrote about the plan, saying we would be the “smallest in North America to build a modern electric light rail system.” Hamilton — the city with a bus system called the “Hamilton Street Railway” — is now working on a plan for rapid transit as well, with a strong citizens’ push for light rail. GO Transit is slated to bring commuter buses to Kitchener in a few months, and trains to Guelph and Kitchener by 2011. The City of Cambridge and the Region of Waterloo are pushing for extending GO trains to Cambridge via Milton.

Most interestingly, in light of the LRT plans here and under the same provincial pressure to grow up and not out, the even smaller city of Guelph is now going to consider light rail in a review of its transit system.

I think as it progresses into the procurement and construction stages, the Region of Waterloo light rail plan will serve to tip transit in Southwestern Ontario to something more serious and more usable. Currently, public transit infrastructure is assumed to be something for large cities (at least in North America), and our plans will show otherwise.

First will be Cambridge, which will be increasingly clamoring for its light rail extension. Other cities and areas — Hamilton, Guelph, London, Brantford — will consider light rail and bus rapid transit (BRT), and people there will know that LRT is a serious option, and that BRT is a pale imitation. Cambridge and Guelph will get some kind of rail link along an existing right-of-way. GO Transit will perhaps provide the missing link between Kitchener/Cambridge and Hamilton. And once the LRT is in place in Waterloo Region (if not before then), we will certainly start exploring additional transit infrastructure, such as to St. Jacobs and Elmira and along cross-corridors.

People in Southwestern Ontario will realize that true, useful, and pleasant transit is possible, and will stop being satisfied with token bus service and congested roads. And the Region of Waterloo will lead the way.

Contradictions in light rail opposition

I just sent in a letter to the editor at the Record:

It is insightful to contrast the two main complaints about the recommended light rail proposal.

Some say that we shouldn’t build expensive and inflexible light rail, that we should spend less money on an expanded bus system. They claim buses are just as good as trains, but are cheaper and more flexible. Well, to say nothing of the positive impact of a visibly permanent route, I will note that people in the real world vastly prefer trains to buses.

Just look at the Cambridge residents angry that they’re not yet getting the train! They’re upset because they’re getting left with only buses, and it speaks volumes about people’s true feelings about them. Those who have the choice will continue to avoid buses, but it is precisely these people who we need to be enticing out of their cars.

I, for one, would prefer seeing trains to Cambridge sooner rather than later. However, if we don’t build light rail at least in K-W, no one will leave their cars, and all of us in the region will bear the resulting costs of sprawl and roads.

Simplicity, light rail, and a more complete transit system

Last night I spoke at Waterloo Regional Council in support of the staff recommendation for a light rail system for the region. The speech incorporates and expands on my earlier draft and on my idea for a more complete transit system for the region. I had several people come up to me to express their support, so I want to share the speech: Read More…

Reality-based transit planning

Discussion, planning, and design of transit systems that aims to get people to use them must be based on what people actually do rather than on what they should do. The more in line with people’s actual use a transit system is, the more useful and economically efficient it is.

It is irrelevant how far people should want to walk to get to transit. The reality is that they are not willing to walk far, though the more complete reality is that they are willing to walk further to get to a train than to a bus.

It is irrelevant that people could plan around infrequent service. Very few are willing to do so.

It is irrelevant that people should take the bus to get to where they need to go. Either they will or they won’t, and empirical evidence all over the world says that they will do everything in their power to avoid buses.

This is why I have been talking about perception and simplicity. Because at the core of a transit system are people who have to navigate it using their faculties of perception and memory (and more), and who also do not derive equal pain or pleasure from the various modes of transportation. Paternalistic transit planning based on what people should do is self-defeating.

The uncertainty of buses

A lot of the issues with regular bus systems can be explained as uncertainty:

You don’t know which route you should take, where to find that bus route, when the next bus is supposed to arrive, how early or late it will actually arrive, and where to get off. The only thing that is generally certain is that you’d prefer not to deal with the uncertainty.

A more complete transit system for Waterloo

The Waterloo Spur alternatives should not be treated as opposing alternatives but as an operations issue which should be seeking to serve both corridors over the long-term. As currently structured, the alternatives create a fundamental choice between a more “hidden” LRT system and one that is open and public along the King Street alignment. There was concern that the physical environment and walking distances in the R&T Park were not currently supportive of transit use, whereas the King Street alignment had the potential to contribute to the ongoing intensification along the corridor and capture ridership from Sir Wilfrid Laurier University. It was noted that if the initial investment were to occur along King Street, a potential branch along the Waterloo Spur could be created at anytime in the future and that this could be tied to development within the R&T Park.

That’s commentary from the expert panel cited in the Region’s recent report on the preferred Rapid Transit plan.

I agree with that assessment, and think that if only one of the routes has to be built at the outset, it should be the King Street route, which connects Laurier, supports development at King & University, and provides for redevelopment potential along the suburban-looking King & Weber area. This is as opposed to the R&T Park, which is huge and spread out, much of it still far from any future light rail station.

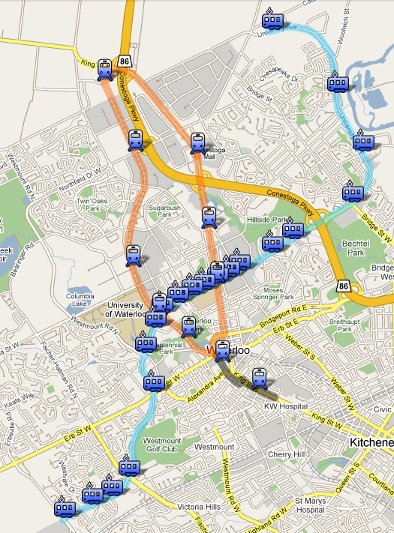

However, I do not believe this is the best way to provide for transit and development in Waterloo. I think both routes should be constructed at the beginning, and furthermore that there should not be a weird and confusing detour from King that there is right now in the plans. Let’s assume that my previous suggestion of keeping both tracks on Caroline in Uptown Waterloo is followed. North of that, half of the trains would return to King, and go all the way up to Conestoga, and the other half would follow the spur line all the way to the St. Jacobs Market, returning via King. This would form a useful loop. See the map at the bottom of this post.

What this doesn’t account for is a connection between the universities. In the current plans there is probably a bus route that runs along there. However, University Avenue, especially in between the two campuses, is an excellent place to create a vibrant street, with nice-looking residences and all kinds of shops and restaurants. The best way to serve the students here is to have a streetcar running along University, as is illustrated in the map. Such a streetcar would also serve the outlying areas in the same way as a feeder bus would — perhaps going to both ends of University Avenue to serve the suburb commuters and connect them to the LRT spine and the universities. It would lead to development elsewhere along University Avenue. Also, RIM Park could in this way become a trolley park. (Back when streetcars were commonplace, streetcar operators might open an amusement park at a terminus in a streetcar suburb to attract riders on weekends.)

I believe my proposal is a much more complete solution to transit in Waterloo than just one branch of LRT. Streetcars make a lot of sense for cross-corridors that are ripe for development of vibrant streets. In Waterloo, University Avenue is such a place. I haven’t studied the rest of the region, but I’m sure that several of the current cross-corridor bus plans could be fruitfully replaced with streetcars. It is probably unnecessary to explain why streetcars are a better driver of development and ridership, so I won’t do it here.

What this means for the current plan is that Council should be encouraged to have it both ways, and to construct both routes. Cross-corridor streetcars can be separate projects, and they can in fact be started immediately. A University Avenue streetcar would make itself useful very quickly.

Simplicity and the case for light rail

On June 10, Regional Council will hold a public meeting about the Rapid Transit proposal prior to the vote on June 24. Below is my current draft speech. Delegations are allowed 10 minutes, so I may expand it a bit.

I have travelled to many cities, both in North America and in Europe. And I can count on one hand the number of times I’ve had reason to ride buses in cities while travelling. On the other hand, I’ve ridden all manner of trains: streetcars, subways, light rail. (Many of those cities were travelled to by car, I might add.) This is because user-friendly bus systems are a rare species.

What I want to emphasize is the ease of use of light rail as compared with a normal bus system. These things have quite different aims: the bus system needs to service an entire area comprehensively, and by definition is complicated. Bus routes may easily change from one season to the next, even those of rapid buses. It is very difficult to know a bus system well. I regularly use buses here, and I know only a few routes that get me around in a limited fashion. For other trips I have no choice but to drive.

A light rail system is a permanent fixture of a city. This has huge economic implications, as potential businesses will know that the train will be exactly there, and won’t get moved. Same thing for people who decide to buy a condo, and consequently for those who build condos. Whatever assurances might be given (and they rarely are) that a bus route will stay fixed, they will never be good enough to actually convince people of the permanence of something so inherently of no fixed corridor.

It is easy to understand a light rail system: there is a small number of distinct, named stations, and there are trains running often enough that you do not need a schedule. You walk to one stop, wait for a train in the right direction, get off at another stop, and walk to where you need to go. There should definitely be shuttles connecting to the light rail stations, but be assured that there will be many more people that would have nothing to do with buses, but who would use the train.

There are clear advantages for any visitors to the area — they can park their car and use the train to get around. They will get off the GO train, or the high-speed train, and easily be able to get to the most important destinations. These visitors simply will not navigate a bus system if they can avoid it, and they will avoid it, either by driving or by just not coming to a place in which buses are the only way to get around.

Of course, there are other reasons why light rail is superior to buses, and these help explain why many people with easy access to a car would use light rail, whereas buses are generally used by those who have no alternative. Modern light rail has a very smooth ride, is quieter than buses and even many cars, and releases no diesel fumes on riders and passers-by. There are many current drivers who would gladly give up commute-driving in exchange for a quiet ride where they can read or nap while not paying for gas or car upkeep. It is also far safer, of course, for them to take the train than the expressway. With a light rail line, the adamant drivers will have fewer cars on the road and the Region will have less danger of running out of space or funds for ever-expanding roads and highways.

I have focused on the simplicity of light rail, but there has to be simplicity in the plan itself. To that end, I very strongly urge Council and staff to reconsider the confusing splitting of the route in downtown Kitchener and Uptown Waterloo. It does not drive development as well as a single corridor and it would not be a comprehensible decision in 20 years. Businesses have been concerned about visibility. However, the proposal is not for a streetcar but for rapid light rail with few stops, and thus accessibility rather than direct visibility is the most important aspect for businesses.

Let me mention one last, but very important issue. If the light rail line is to be staged, the bus stage for the Kitchener to Cambridge segment must be very temporary. There is little simplicity, and even less ease-of-use in a line composed of both a light rail and a bus segment. The region must make a firm commitment — either in terms of year or ridership — to building the Kitchener to Cambridge light rail portion. This is not just a concession to Cambridge, but what needs to be done to make this project the best long-term solution it can be for our region.

By this point it should be clear how important it is to have a fixed-rail line connecting our cities and their major destinations. Of the possibilities, subways are too expensive, elevated systems are too intrusive, and buses are inherently impermanent. We must choose to build light rail to move this region forward.