The future is multi-nodal

TriTAG's map of the LRT (red) and planned express bus routes. The line is more interurban than it is CBD-to-suburb.

My last Record column this year evaluates the idea of the central business district in the context of Waterloo Region, and (of course) again discusses light rail. Hopefully it isn’t too unfocused:

The Future is Multi-Nodal

Commentary on the light rail transit project reveals a common but outdated assumption that a city should have a central business district (CBD) — an area of downtown that no one lives in, but many commute to from the suburbs. A frequent argument against the project is that downtown Kitchener isn’t a large enough CBD and that there aren’t enough people commuting in. But the whole concept of a central business district is a thing of the past, and light rail does not need a large CBD to make sense. The future lies in urban areas composed of multiple dense nodes connected by high-quality transportation — which happens to be exactly what Waterloo Region is planning for.

Cities once contained housing in addition to commerce and industry. When streetcar lines were started, they moved people within the city, but they also opened up the suburbs for residential development that promised tranquility and fresh air. Later, the availability of cars and cheap fuel together with massive post-war highway and road development led to suburban flight on a larger scale. Commerce also followed the highways and set up shop in suburban malls. Only jobs remained, producing the classic CBD — where commuters stay from 9 to 5, leaving an empty city every evening. But those long commutes aren’t healthy for our cities, and an office monoculture is not conducive to urban living.

Most of Waterloo Region’s growth has occurred after the post-war years, and many jobs are located in suburban office parks. So we have no reason to cling to the notion of a CBD — it just doesn’t apply. But that’s not a bad thing. Instead of jobs clustering in any single downtown, many destinations and much employment have fortunately clustered along a reasonably dense linear corridor.

Growing Waterloo Region up with transit infrastructure

My Record column today makes the case for light rail in Waterloo Region, with a slightly different approach than last year’s one:

Growing Waterloo Region Up with Transit Infrastructure

A single line of built-up areas is easily seen in Waterloo Region satellite imagery — this is the Central Transit Corridor. The planned light rail line and the express bus line to Cambridge would connect four downtowns, the university district, three major commercial areas, and many corporate and industrial campuses — along with a quickly growing supply of housing. In the context of a redesigned bus network and strong planning policy, LRT (light rail transit) is the infrastructure necessary to manage growth and provide for the region’s economic and environmental health.

Most of the tremendous post-war growth here has been suburban, but the area near the LRT route has still grown by 50% or more since 1955 — the last year of interurban trains. If that was it, light rail wouldn’t make sense. But the plan looks to 2031, and the province projects more than 200,000 new residents by then. The Region’s new Official Plan implements provincial targets of 40% of growth occurring in the urban cores. This will more than double the population and jobs along the Central Transit Corridor. A light rail system will both help attract this development to the downtowns, and handle the resulting demand for transit along the spine of our region. It would also be a more environmentally and financially sound approach than ramming wider roadways and more parking into our downtowns.

Many have called for more buses instead of rail. But this isn’t either-or. In fact, the recently approved Regional Transportation Master Plan calls for a dramatic ramping up of the Grand River Transit budget — tripling per-capita funding within twenty years. The plan calls for five new express bus routes in the next five years to service other major corridors, for more frequent and later service, and a redesign of bus routes to a more grid-like network to connect with the light rail and the express routes.

However, simply more buses won’t work in the Central Transit Corridor. Already, each direction of King Street between Waterloo and Kitchener sees 12-15 iXpress and Route 7 mainline buses an hour. Which is great for riders now. But when the population and jobs more than double, so will transit ridership — or actually more without road expansion. With buses as they are now, 20-30 buses an hour is essentially the limit. Past that point they bunch together and form jams at busy stops. For them to handle the ridership we would need a bus highway through our downtowns, with passing lanes and level platforms. For most of the cost of an LRT system, it would get us dozens more buses per hour polluting our downtowns with diesel fumes and noise, and would only postpone the capacity issues.

LRT, in addition to its smoother ride and quieter and friendlier electric propulsion, has larger vehicles that can be coupled in trains. Less manpower is needed to operate it, and more and bigger doors allow for low dwell times at stations — which are the main capacity bottleneck. And more than just funneling growth into central areas, the inflexibility of light rail will be able to guide development to occur alongside transit and in a way conducive to transit use.

We’re finally realizing that our resources are finite. In the post-war era, anything was possible. Technology would solve all problems, land was plentiful, gas was cheap, and everyone could drive their car from the idyllic suburbs to work downtown. We know now that sprawl comes with costs to the environment, costs to our health, and costs to our wallets — it’s expensive to build streets and lay down infrastructure to serve low densities at the edge of the city. We’ve already chosen to put a limit to sprawl. Now it’s time to follow through with the transit service and infrastructure that will grow our Region up and not out.

Twelve reasons why vehicular cycling isn’t enough

We often hear that cyclists should follow the rules of the road, just like motor vehicles. Since recently obtaining a practical city bike I have been using it as my primary means of transportation — and have mostly been following those rules. But as helpful as the techniques of vehicular cycling are, it has become quite clear to me that this model of bicycles sharing space with cars is generally inadequate as a model to encourage regular use by regular people on bikes.

Those rules of the road in North America were explicitly designed to facilitate automobile travel. But bicycles — and particularly city bicycles — are not cars, and they generally cannot travel on the same road as fast-moving cars and trucks in a way that is convenient and subjectively safe.

Bicycles are slower, much smaller, quieter, and generally less visible than are cars. They pose virtually no hazard to the occupants of a motor vehicle, and little hazard to the vehicle itself. In North America, they are also unlikely to pose any financial or legal hazard, as unintentionally hitting a cyclist does not usually result in any consequences. (Amazingly, you can even intentionally hit cyclists with no jail time.)

I believe that a number of routine car interactions are dependent on the threat posed by other vehicles on the road — gut feelings being the real driver, as in so many other situations. Naturally a motorist does not feel threatened by a bicycle on the road as he does by another vehicle, and thus a cyclist has difficulty navigating road situations which implicitly rely on that threat.

Here are a few specific reasons why and situations in which vehicular cycling poses problems, due to visibility, speed, and that lack of threat. (Left and right are in the context of right-hand traffic.)

1. Left turns at intersections without signals or left turn lanes. If there’s any traffic travelling in the same direction, you’ve got problems. How do you make it across fast-moving lanes of traffic to get to the left-most lane to make the turn? How do you know that cars coming up from behind will see you when you’re standing there waiting to make the turn? Do you have enough time to make it across during gaps in traffic? Are motorists behind you getting pissed off and starting to pose a hazard?

2. Left turns at conventional signaled intersections. Here there may well be a left turn lane, but again, how do you get to it across multiple lanes of traffic? If you have to yield to opposing traffic, can you find a gap in traffic? If you go when the light turns red to avoid getting stuck (as motorists will do), do you have enough time to cross — and are motorists who just got green on the intersecting road going to be angry at your low speed?

3. Roads with blind curves. Cars travelling at speed around curves pose a serious danger to slow-moving, small (and thus poorly visible) bicycles. Unlike faster-moving vehicles, bicycles are more likely not to have been seen prior to the curve.

4. Obstacles in the right-most lane or bike lane, including gutters, debris, and parked vehicles. Traffic in the next lane over is likely moving much faster. How do you get into that lane?

5. Merges into a lane with high speeds or heavy traffic. Here a car can accelerate to speed and/or force its way in. The speed and threat imbalance make either a difficult proposition for a cyclist.

6. Trucks and buses. Drivers of large vehicles have poorer visibility of the area around the vehicle, and so are particularly likely not to notice a bicycle. They are also less able to judge how close the bicycle is.

7. The encouragement to ride faster and to accelerate faster. Car speeds set a norm for the speed of road travel, and the slower you ride, the more impatient drivers will be with you. On the other hand, the faster you go, the fewer times you will be passed by cars (often too closely for comfort). Going fast and accelerating quickly are counter to the normal inclination when riding a city bike for utility without cycling clothes or needing a shower at the end of your ride.

8. Riding side-by-side. This natural and pleasant way for two people to ride somewhere together is incompatible in philosophy and practice with vehicular cycling.

9. Stop signs. Setting aside the fact that motorists themselves often don’t come to a complete stop, there is no good reason for cyclists to come to a full stop at a stop-controlled intersection. On a bike one can get very good sight-lines by slowing down at an intersection, but without losing all momentum. (This is known as an Idaho stop.)

10. Tight left turns from an intersecting street. We all love to cut corners, and motorists are no exception. When turning left, they often cut into the cross-street’s left-turn lane if they don’t see any cars there. A bike in that lane is less visible and less expected, and thus in danger.

11. Cars merging from the left on a road without bike lanes. If a car travelling closely behind another car in the left lane decides to merge right, slow-moving and small vehicles (e.g. bicycles) can be obscured by the car in front.

12. Multi-lane roundabouts. If you’re staying on the roundabout past a two-lane turn, you’re either in the right lane and liable to get hit by a car turning from the left lane or you’re in the left lane and liable to get hit by a fast-moving car.

If you’re fast enough, sufficiently trained, and aggressive enough, you can probably navigate the above scenarios on the busiest of suburban arterials. But most people want neither to be particularly fast nor aggressive, nor to undertake difficult training in traffic. They want to travel safely and comfortably, with their stuff, and without breaking a sweat.

Vehicular cycling is a marginal activity, barely visible and taking place on small pieces of car-dominated roads. It is a coping mechanism for cycling-inadequate road infrastructure designed for cars. Its techniques are useful for making do with what we have, but it is useless as a model for promoting cycling as an everyday mode of city transportation for regular people. If we want people to cycle in large enough numbers to make a difference in our cities, we have to acknowledge the serious differences between bicycles and cars — and for that matter, between bicycles and pedestrians — and implement segregated cycling infrastructure. Especially on roads with high speeds or many large vehicles, and at intersections.

Taxpayer money should fund transportation efficiently

My latest Record column is on the public subsidies for highways:

Taxpayer Money Should Fund Transportation Efficiently

Today’s lesson in economics: When something good is free, people take more of it. But if it’s the government handing out the free lunch, you better believe you’re paying for it. Space on provincial highways like Highway 401 is one such free lunch, and it’s often painfully clear to motorists that this space is in high demand. Much of that demand is thanks to the taxpayer subsidy for highways.

Insufficient road capacity has been a perennial problem ever since we started driving everywhere and choosing where to live based on road connections. The perennial solution has been to add new roads and widen, widen, widen — neighbourhoods and the environment be damned. It hasn’t worked, however, thanks to the phenomenon of induced demand. Once a busy highway is widened, it only takes a few years before people move in to new, cheap houses further out along a clear commute — and the highway gets congested again. Taxpayer money is thus spent to turn the problem of traffic congestion into two problems: traffic congestion and more infrastructure to maintain.

As crumbing bridges across North America can attest, we haven’t even kept up with the maintenance of our existing road network, much of it built in the 1960s and 1970s. Every new overpass is an overpass that has to be replaced in 40 or 50 years. Every new lane of roadway is an extra lane to repave every several years. More space on the roads results in more driving, leading to the lost productivity costs of congestion and more injuries sustained and lives lost in the lane of duty (with attendant emergency response costs). And, of course, more driving costs the environment through desperate oil production, carbon release and air pollution. Highway spending nets us a much larger bill than we bargain for.

The financially sustainable solution to congestion requires providing transit that is sufficiently good to attract drivers. Transportation by rail uses fewer resources to carry more people, and arguably in more comfort. The infrastructure requires less maintenance, lasts longer, and is lighter on the environment and public health. All costs considered, train service is less expensive than building and maintaining more highway space.

Commuters’ decisions are based mostly on the personal costs and benefits of the choices available to them. They have no great love of driving on busy highways (even free ones), but they can’t take an alternative that doesn’t exist. When presented with serious alternatives to driving, commuters flock to them in droves. The popularity of commuter rail, such as GO trains, indicates that plenty of people would choose to get to work by train.

Instead of spending double-digit billions on further highway expansion, Ontario should funnel transportation funds into train service, such as GO train extensions to Kitchener and to Cambridge, the Waterloo Region light rail project, and frequent and fast train service on the Quebec City-Windsor corridor. With good alternatives in place — which could even be as simple as dedicated bus lanes — Ontario should implement dynamic user fees on limited-access highways to pay for upkeep and to eliminate congestion.

Some would take the train and others would take the bus on those same highways. Yet others would move closer to work — like the three-fourths of Waterloo Region commuters who travel less than 10 km to work (and who currently subsidize those long highway commutes). Of course, occasional and regular users who find the highway worth paying for would have a faster, congestion-free commute.

Limited-access highways are at best a wasteful kind of transportation infrastructure, but when congested they are a tragic waste of economic resources. If we believe in subsidizing transportation systems, we should be doing so efficiently, and doing it to improve overall quality of life.

Gridding UW: A new street plan for the University of Waterloo

In a previous post I described how the University of Waterloo fails its pedestrians. But UW’s problems go deeper. It was built as a suburban campus on farmland in the 1960’s and 1970’s — when it seems planners and architects were intent on planning for the car, even when designing a pedestrian-dominated place. Now that the campus is surrounded by the city on all sides and there is growing recognition that spaces need to be designed for pedestrians, it is important that it integrate well into its environment. However the campus street plan essentially does the opposite.

Currently the main campus road, Ring Road, is accessed by vehicles only through two connector roads on the north and south. There are thus a high number of intersections for vehicles to contend with, and it is a roundabout trip to get in and out of the campus. My estimate is that most of the people travelling by motor vehicle on Ring Road are actually using transit. So the meandering is a waste of time particularly for bus riders and of money for Grand River Transit (as UW is a transit hub). But even though Ring Road is difficult to get to, it is wide open in many parts and even the few speed humps don’t suitably slow down car traffic.

UW can be a pain to get to on foot from some directions, and difficult to navigate once you do. There are barely any pedestrian thoroughfares, mostly just paved paths (if that). In many cases, vehicular access roads serve as makeshift pedestrian corridors. All parking is surface parking, and there are lots right inside the main campus (bounded by Columbia and University).

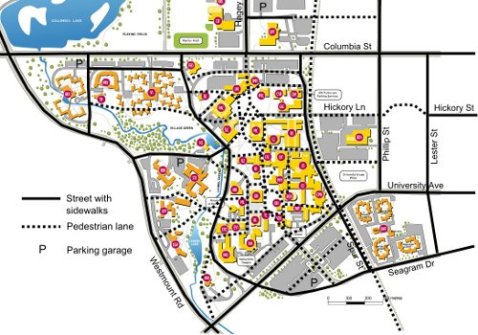

The current UW campus, based on an official map. Solid lines are roads, many with missing sidewalks. Dashed lines are pedestrian paths that are wide, specially paved, or otherwise deliberate.

I propose a new University of Waterloo street plan. With contribution from Sylvan Mably, I’ve drawn what I think to be a much improved version of UW’s campus. The emphasis is on connectivity, navigability, and a street system that fits its use. This alternative street plan is ambitious but firmly rooted in what is actually feasible to do from the current situation.

There would no longer be a Ring Road, and its east and west segments would be through streets. Moreover, both of these streets would connect with Seagram Drive at the south end of the campus, and part of the current Seagram alignment would be turned into a pedestrian thoroughfare (as it would not be a useful vehicular connection). Other notable road changes are an extension of the current St. Jerome’s access road across Laurel Creek to the extended Seagram Drive, and a street connection for the west end of the student village. Good road connectivity would reduce the distance vehicles (including bicycles) need to travel to reach points of the campus.

The solid lines on the map would be streets with wide sidewalks and perhaps bike lanes. As the design of a road dictates how drivers use it, through streets inside the campus would be designed for low speeds (30 km/h). Where possible, they should have street parking with demand-responsive pricing; this would ensure that short-term parking is available when needed. The dashed lines are what I call pedestrian lanes. These are wide thoroughfares laid out with paving stones and designed for pedestrians, but shared with cyclists and the occasional intruding campus delivery van. These lanes should be named, especially the several that provide east-west routes and the north-south thoroughfare (which splits around the Grad House knoll and the Math & Computer building). With naming and a somewhat grid-like network of lanes and streets, the navigability of the campus would improve dramatically. Wayfinding and campus travel would become easier and more pleasant. Thanks to improved connectivity, the campus would be easier to access by walking, cycling, bus, and light rail (which will stop along the east side of campus).

Most of the lanes follow existing paths, but some would need to be graded first and others would need to be created through current parking lots. A connection would be made between Lester and Phillip Streets to make Hickory Street/Lane a useful corridor across UW, through the Northdale neighbourhood, and past King Street. Two buildings would have to be sacrificed to open up the north and south pedestrian gateways to the campus. The more pressing one is South Campus Hall at the south gateway, and the current campus master plan actually calls for it to be demolished for this very reason.

Endless construction has been steadily devouring what little open space UW’s main campus has left. There are currently grand plans afoot to develop distant parts of the University of Waterloo lands, possibly including academic buildings. My plan would allow well-located possibilities for street- and lane-facing campus buildings to accommodate growth, in particular at the parking wastelands in the north and south ends. UW is actually already haphazardly removing lots to put up new buildings. With my street plan there would be opportunities for well-located parking garages, e.g. by St. Jerome’s, off Seagram Drive, or by Columbia Street. It would also open up important possibilities for public space, such as around the south gateway to campus. Eventual demolition of some of the old three-story buildings in the center of campus (and replacement with taller, more compact ones) would allow for some much-needed central public space.

This is intended to be food for thought, and is neither exhaustive nor definitive. However, I strongly believe that a plan along these lines would dramatically improve the University of Waterloo’s walkability, connectivity, campus experience, and safety, and make it a better university overall.

Down with “avid cyclists”

As if it wasn’t enough that we scare people away from cycling with our exclusively car-oriented infrastructure and even a socially constructed fear of cycling, we also do it by marginalizing cycling as something done only by the kind of people who cycle. Make a mental count of how often you’ve seen news reports or commentary refer to “avid cyclists”, and the number of times you might have used this term yourself.

Banish “avid cyclist” from your vocabulary. Self-marginalizing language like this is why we can’t have nice infrastructure.

By using and condoning the use of this term, we help reinforce our tendency to neglect the impact of the situation and over-attribute behavior to characteristics of the person. In other words, labelling those who willingly cycle as “avid cyclists” is a way of setting aside the difficult and interesting problem of how to make our cities conducive to cycling — in favor of the easy story of cycling as something “other”, as something done by people who aren’t normal. Why bother making the city a better place to cycle if the only people who will do it are the ones who are already cyclists? Why waste city money on them?

Note the division into us (normal people) and them (avid cyclists). Never the twain shall meet. Is that true? No it is not.

I claim that in most North American cities, while you will find many people riding a bicycle for utility/transportation, most people who cycle are hardly avid. Do they cycle in the dark? Do they always cycle on the road? Do they cycle in any part of the city? At any time of year? The answers are an emphatic no. And the reason is that the majority are cycling when the situation makes it easy and attractive for the person who considers the possibility. Avid cyclists should be resilient cyclists, but actual North American cyclists are fickle. With their recreational bikes and the poor infrastructure they have access to, they are fair-weather, back-roads cyclists.

Some places seem so far into the motor kingdom that cycling as transportation appears patently absurd to many. Thus, to brave the unfriendly conditions, cyclists must be avid — doing it as a sport, as exercise, to prove a point. Yet this describes fewer places than you think. I know it absolutely doesn’t describe Kitchener-Waterloo, Ontario, however “avid cyclist” still seems to be the mindset here.

There is a poignant irony in the number of obituaries a search for “avid cyclist” turns up. If instead of marginalizing cycling, we facilitate it through infrastructure and encourage regular people to ride, fewer people will die on the roads and those who cycle will be healthier for doing so. We need to free cycling from the shackles of recreation. We need to get utility bicycles into our bike stores. And instead of the conversation being about cyclists, we need to make it about regular people taking advantage of the two-wheel mobility available to them — because it is effective and enjoyable.

Addendum: There are more comments on this post over at Copenhagenize.com and Kaid Benfield responds as a proud avid cyclist.

The fundamental attribution error in transportation choice

In social psychology, the fundamental attribution error refers to the tendency for people to over-attribute the behaviour of others to personality or disposition and to neglect substantial contributions of environmental or situational factors. (Actually it isn’t quite fundamental, as collectivist cultures exhibit less of this bias.) People are generally more aware of the situational influence on their own behaviour.

Thus, the fundamental attribution error in transportation choice: You choose driving over transit because transit serves your needs poorly, but Joe Straphanger takes transit because he’s the kind of person who takes transit. This is the sort of trap we find ourselves in when considering how to fund transportation, be it transit, cycling, walking, or driving.

Let’s say you live in a suburban subdivision. You can afford to drive, and it’s the only way you can quickly and easily get to your suburban office and to the store, and pick up your child from daycare. How do you interpret the decision of other people to take transit? Is it something about the quality of transit where they are? More likely you are going to attribute it to something about those people themselves — they’re poor, or they’re students, or they’re some kind of environmentalists. It’s difficult for people to realize the effect of the situation, e.g. one with frequent transit service to many destinations along a straight street that is easy to walk to. (I’d also point out that students, the poor, and even environmentalists do drive as well.)

Why do Europeans walk more, cycle more, and take transit more? Surely it is something about their culture? But this is an excessively dispositional attribution. I won’t deny that culture plays some role in transit use, especially in the decisions that lead to the creation of transportation infrastructure. But that infrastructure itself and the services provided on it are a strong influence on the transportation choices people make. The European infrastructure situation facilitates those other modes of travel much more so than does typical North American transportation infrastructure.

Where our infrastructure gets closer to the European model, so does the transportation mode choice, and conversely, where Europe is more like the North American model, Europeans turn out to drive more. If culture were really the driving force, you wouldn’t expect to see much fluctuation in transportation choice. But just as North America suburbanized and fell in love with the private automobile, so did Europe, albeit to a lesser extent. Only recently has Europe started again building new tram lines and clawing back space from the car. Copenhagen, now viewed as an urban cycling mecca, wasn’t always one. The rise of the car drastically lowered cycling there in the 1960s. Copenhagen owes its recent fame to restrictions on parking and to its dedicated cycling infrastructure, which have led to a cycling renaissance.

Consider how North American visitors travel in Europe. How do they get around London? The Underground. How do they get between London and Paris? The train. How do they get around Amsterdam or Copenhagen? Quite possibly they rent a bike. When in Rome, they do as the Romans do: they walk, take the subway or tram, or maybe ride a Vespa. What do European tourists do in North America? Generally they rent a car, because that’s the only realistic way to travel in most places. There are exceptions, of course: tourists to New York City or Washington, D.C. take the subway because that’s the most convenient way to travel in those cities.

We’re not so different from tourists in how we choose to get around. We may have our own preferences, but the biggest influence on our choice of transportation mode is what modes are available to us and how useful they are. Above all this is determined not by culture and personality but by the kind of infrastructure and transportation service provided.

Addendum: Jarrett Walker has some great commentary on this post at Human Transit. More context was given in the Streetsblog write-up. Cap’ Transit provides a counterpoint, and there’s more commentary at Kaid Benfield’s blog.

Another perspective on the Iron Horse Trail

This post is cross-posted to the TriTAG blog. Go there to leave any comments.

It can be insightful to take another perspective on something we’re used to. Yesterday I walked the length of Kitchener-Waterloo’s Iron Horse Trail and photographed it from its most common vantage points — the roads crossing it. There is little immediately evident in these photos, but I will explain below. Read More…

The curse of flexibility in transit

You hear it all the time. Buses are more flexible than rail. From point A, bus routes can take you to your favorite points X, Y, and Z, each in a single ride. They can detour around an accident. The routes can be altered to accord with population shifts.

But the curse of flexibility is that it gets used. It sounds like a truism, but bear with me. I believe the theme applies rather broadly, but I want to talk about the curse of transit flexibility.

The other day I was at the University of Waterloo after 7 pm and had to unexpectedly make it to downtown Kitchener. The 8 bus could get me there, but it was running at a 30 minute frequency. By that hour the 7 was running at a 30 minute frequency, on just one of its routings. The iXpress had the furthest stop and at that hour was also at a 30 minute frequency. I had the luxury of a choice between three different buses with separate schedules and bus stops — and infrequent service. Had the iXpress been running at a 10 minute frequency, I would’ve gone to that stop and not have wasted my time and energy trying to plan such a simple trip.

In contrast, transit infrastructure like light rail forces a choice of a corridor — and that’s where the service is concentrated, without being diffused among many routes.

Buses can detour. For some time this week road construction closed the north UW campus entrance, and separate construction closed the east side of Ring Road. That meant hell for transit users, who first had the realization that their bus wasn’t where they expect it, then had to figure out where it actually was, and of course the schedules were screwed up anyway. The iXpress did a detour of over 3 km between the UW stop and the R&T Park stop, taking a long time and getting stuck in the construction-related traffic along the way. Getting out and walking that same distance would have been faster.

Light rail can’t detour, so it forces construction to be done quickly, with minimal impact — and at night whenever possible.

Buses can have their routes moved in accordance with change in transportation demand, and the flip side is the absence of commitment that transit along a corridor will be provided in the years to come. So the location of transit routes cannot be used to directly inform decisions about where to live, or where to build. If you build fixed transit infrastructure (e.g. light rail), however, it’s a self-fulfilling prophecy. There is a tangible commitment to providing transit along that corridor, which is used to determine where to live and where to build, thereby itself shaping the transportation demand.

Precisely due to their flexibility, buses can do little to shape or direct urban form and land use. So they have no choice but to react. They can demand little of any forces that hinder their operations. And a bus system’s flexibility in providing service from any point to any other point makes it difficult to consolidate service into select, high quality routes that are easy to understand and use.

Good ideas: Permeable pavement

Most pavement is impermeable to water. As a result, paved surfaces need to be designed to funnel water into drains, and drainage and sewer systems need to be designed for the high capacity necessary to deal with runoff from the huge number of paved surfaces in our cities. Instead of replenishing groundwater, precipitation is redirected to rivers and lakes. Runoff from roads carries with it automotive pollution, which is then concentrated in downstream bodies of water.

Various technologies are coming into use, however, for pavement that is permeable to water. Porous asphalt and pervious concrete are fairly new techniques, so they are still being developed and improved. The main difficulties include weight resistance and longevity, as well as cold climate installation. And, of course, it’s more expensive to install (particularly for cold climates), though it may be cheaper than conventional pavement if considered together with the costs of storm-water management.

What’s the point? First off, urban runoff is reduced, and with it pollution and the need for large and extensive drainage systems. But there are other benefits that I haven’t seen mentioned elsewhere. On impervious road surfaces drainage can work poorly, leading to the sometimes hazardous accumulation of water, which could be averted by permeable pavement. Likewise, it can prevent the ubiquitous puddles that form in depressions on sidewalks and paths. This pavement can also eliminate the need for drainage grates that are often encountered on bike lanes, which can be a hazard and nuisance to cyclists. If pervious concrete is used, it has the added advantage of reflecting more sunlight than asphalt, which can have a significant mitigating effect on climate change.

The technology is promising and I am surprised that the Region of Waterloo hasn’t yet taken up the idea. The Region should investigate permeable pavement and at least pilot the technology. They could do worse than paving the path through Waterloo Park as a test.